Devil and the Deep (1932)

Island of Lost Souls (1932)

Advise and Consent (1962)

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939)

[6]

Charles Laughton’s performance as Quasimodo is the main reason to see this movie. Laughton gives the deformed bell ringer moments of quiet torment as well as unbridled joy, and without ever going over the top – a remarkable feat that should have earned him an Oscar nomination. I also liked Cedric Hardwicke as the malevolent Frollo and Maureen O’Hara (in her screen debut) as Esmerelda, but several of the other cast members act as though they are playing cartoon characters (Harry Davenport is the worst offender). The film could have benefited from a more genuine period setting and a more earnest supporting cast. Director William Dieterle bestows the film with some elegance, though it’s not nearly as polished as his later work on The Devil and Daniel Webster.

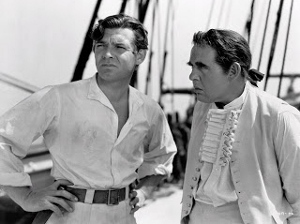

Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)

[8]

You know you’re in for a harrowing journey when the ship’s captain gives a dead man 300 lashes before the ship even leaves port. Charles Laughton steals the show here as the torturous Captain Bligh, a greedy monster who plays recklessly with the lives of his crew. Clark Gable is charismatic as Fletcher Christian, the man who leads the uprising against Bligh (and without his trademark mustache, since facial hair wasn’t permitted in the Royal Navy). Franchot Tone is very good as Roger Byam, a friend of Christian’s who ultimately sides with Bligh… a decision that nearly costs him his life. All three actors were Oscar-nominated for their roles, and the film won the award for Best Picture.

Spartacus (1960)

[8]

Fans of Ridley Scott’s Gladiator might be surprised how much they will also enjoy (perhaps even prefer) its progenitor. Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus is a briskly-paced epic, and uncharacteristically emotional compared to his other work. Kirk Douglas is iconic in the lead role, playing a slave forced to fight in the gladiatorial arena for the enjoyment of the aristocracy. Of course he falls in love with a fellow slave girl, of course he escapes, and of course he leads a mammoth army of slaves in revolt against Rome… but when these broad strokes are painted so earnestly, I don’t care. The bleak, bold final act of the film is what really sells the story for me.

The Night of the Hunter (1955)

[10]

Two small children run for their lives from a murderous preacher in the only film actor Charles Laughton ever directed. The Night of the Hunter is a unique blend — part fable and part thriller, both pastoral and horrific, a beguiling mixture of qualities that usually mark the work of an amateur… or a genius. Laughton is as precise and purposeful as Orson Wells (even using Well’s cinematographer from The Magnificent Ambersons), but there’s also a naive, experimental quality to the film, in the way he mixes realism with German expressionism, and solemnity with odd moments of Tex Avery-style comedy.