[6]

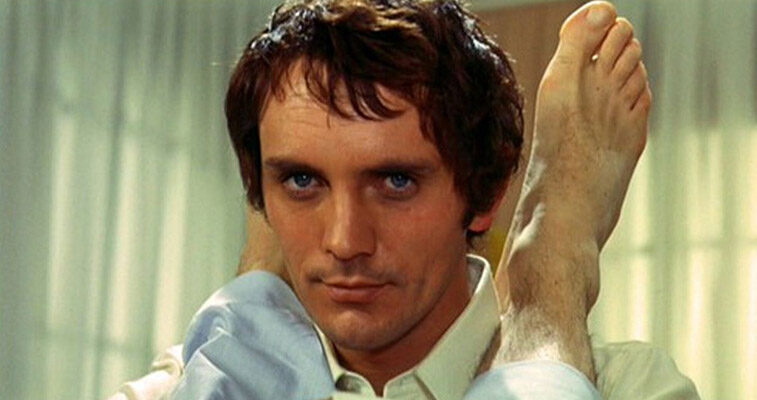

Italian writer/artist/political activist Pier Paolo Pasolini (Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom) paints a bleak portrait of middle-class complacency in Teorema, the story of a bourgeoise household seduced and forever changed by a mysterious stranger played by Terence Stamp (Billy Budd, The Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert). The entire family — father, mother, son, daughter, and even the maid — experience newfound sexual urges in his presence. They submit to him without any effort at all on his part. But after he leaves, each character suffers from their own kind of painful withdrawal, unable to resume the lives they knew before.

There’s a part of me that could easily dismiss Teorema as pretentious art-fuckery. Pasolini pounds the viewer over the head with messages about social class, consumerism, and sexuality. The first half of the movie has some interesting dialogue-less scenes of characters experiencing their ‘awakenings’, but it almost falls into an episodic rut with Stamp having to share the same sort of encounter with five different characters. The mid-mark of the film is its least artfully rendered. After watching half of a mostly silent movie, all the characters wax on and on to Stamp’s character about how he’s changed their lives. But once he’s gone, the film becomes much less overbearing and much more open to interpretation.

The son becomes an artist, the daughter goes into catatonia, the mother (Silvana Mangano) becomes a whore, and the father (Massimo Girotti) starts cruising for men in public places. And the maid? Well, she starves herself to near death, floats in the air, and then demands to be planted in the ground. What does it all mean? I’m not sure anyone knows for sure, except that Pasolini seems to think the nuclear family can’t survive a dash of sexual chaos intact.

Teorema is a strange film that defies conventional narrative and certainly challenges its viewers. I don’t like when Pasolini preaches to us with pointed dialogue and unsubtle uses of Mozart’s Requiem. His silent moments are more effective in getting us to contemplate what his message might be. The second half of the film is redemptive, though. As increasingly confusing and bizarre as the movie becomes, I like the sandbox Pasolini is playing in. Seeing how the characters grapple with the fallout from their sexual indiscretion is something I can get into. And the final shots of Massimo Girotti wandering nude through a barren wasteland, falling in and out of shadow as smoke blows overhead — is some mighty powerful imagery.