[10]

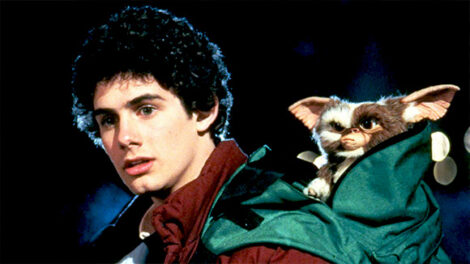

Does it mean anything that Gremlins is my favorite Christmas movie? Am I bad person because I eschew the sentimentality of It’s A Wonderful Life for the malevolent rampage of little green monsters? Actually, sentimentality plays a big part in my love for the film. With its corny premise and comic book violence, Joe Dante’s film is an unabashed homage to the low-budget horror films of yesteryear. While it takes itself quite seriously at times and does manage to achieve some scary moments, Gremlins is never without its sense of humor, the result of which is a hybrid film that defied the studio’s expectations and spurred a legion of imitators.

It was Steven Spielberg who solicited Joe Dante to direct Chris Columbus’ script. Two years earlier, Spielberg had achieved notoriety for stepping on director Tobe Hooper’s toes during the filming of Poltergeist, another Spielberg production. Fortunately for Dante, Spielberg would be away filming Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom during most of Gremlins‘ production schedule. This didn’t, however, keep Spielberg from heavily influencing a major script rewrite. Columbus’ first draft was a far, far darker one, with Billy Peltzer’s mother getting decapitated and beloved Gizmo becoming a monster. Many would argue that Spielberg diluted the concept by making Gizmo a more prominent figure and lightening up the tone of the film, but Gremlins was nonetheless a smash hit with wide appeal. Even in its watered-down state, Gremlins was only green-lighted by the studio because of Spielberg’s involvement. All through production, Warner Brothers didn’t know what to do with the film, uncertain of whether to market it as horror or comedy. The result was a series of abstract ads that piqued the public interest (that and, of course, the words “Steven Spielberg presents” at the top of the one-sheets). It was only in post-production that the studio saw a rough cut of the film and realized the commercial appeal of the film. With cute little Gizmo as their poster boy, and gremlin action figures to make money from, Warner Brothers quickly turned the film into one of the most unlikely marketing phenomena of the 1980s.

The wide appeal and commercial push made Gremlins a controversial movie. With Spielberg’s name and Gizmo’s cuddliness, many were enticed to see the film without realizing it had a mean streak. The violence pushed the limits of what was acceptable in a PG-rated film. The sequence in which Billy’s mother is forced to defend her kitchen against invading gremlins was the most sensational in the film, ending in one gremlin getting slaughtered in a blender and another exploding in the microwave. The backlash lead Spielberg himself to lobby for a new rating that the Motion Picture Association of America adopted shortly thereafter – PG-13.

Controversy aside, Gremlins is the ideal high concept movie. You remember the rules. Keep them out of the light. Never get them wet. And never feed them after midnight. If you break the rules, a bunch of nasty critters will wreak havoc on your hometown during Christmas Eve. As we all know, rules are made to be broken. There wouldn’t be a movie if they weren’t. Director Dante knows the exploitation value at work here, and takes advantage of it by staging such memorable scenes as the gremlins’ snowplow attack on the Futtermans, Mrs. Deagle’s accident on the stair crawler, and the debauchery at Dory’s Tavern. Dante lavishes several minutes of screen time on the later, almost creating a movie within a movie that focuses entirely on gremlin behavior – how they play cards, how they drink beer, and just how far they’re willing to go for their own self amusement (hint: it involves firearms — you probably wouldn’t see such a display today).

While Gremlins is primarily a clever and entertaining exploitation film, it’s a little bit more sophisticated than your average B-picture. At the time the film was made, the marriage of comedy and horror, though experimented with in independent films like The Evil Dead, was still largely unexplored territory for the studios. Gremlins works hard to interweave the two, so much that the audience sometimes doesn’t know whether to laugh or scream. After escaping Dory’s Tavern and finding refuge in the ransacked bank, Kate (Phoebe Cates) tells Billy (Zach Galligan) why she hates Christmas. As fires burn in the background and composer Jerry Goldsmith performs a subdued rendition of “Silent Night”, Kate shares the story of the time her father dressed up like Santa Clause and tried to surprise her by coming down the chimney with an arm full of presents. He slipped and fell and broke his neck. The body wasn’t found for days. It’s a tragic story, but such an outlandish way to die, that we watch the scene not sure what to think of it. Is it supposed to be funny? Is she serious? Is this whacky movie trying to pull the rug out from under us? This ambivalence was by Joe Dante’s design. The scene embodies his intentions with the film, that of mixing the funny with the frightful.

Films like Gremlins, because of their overwhelming entertainment value (if I do say so myself), are often criticized for being devoid of any nuance or interpretation. I do not think this is necessarily a bad thing, nor entirely true. The writing and directing of Gremlins is remarkable in how it achieves its balance of tone. Consider the film’s town of Kingston Falls, where everybody knows everyone. Everyone’s parents proposed at the local tavern, mom makes gingerbread cookies, and Snow White‘s playing at the local movie house. It’s the idealized American traditional home town. To emphasize the importance of this environment, Dante chose to shoot Gremlins almost entirely on studio back lots and sound stages, which together with John Hora’s highly theatrical lighting, gives the film a not-quite-real feeling. The plasticity of the film’s world makes it suspect, and indeed, it has its dark side. Most of the town’s people are struggling to make ends meet while the greedy Mrs. Deagle (Polly Holliday) works with the bank to foreclose on everyone’s mortgage loans. Billy Peltzer (Zach Galligan) is working a dead end job at the bank and practically supporting his entire family. This is the environment, phony and troubled, onto which the gremlins are unleashed. The “virginity” of the town makes the gremlins’ antics all the more appalling, as highlighted in scenes like one in which a gremlin attacks Billy’s mom (Frances Lee McCain) from inside a Christmas tree, or in the imagery of a gremlin hiding among children’s toys. The gremlins prove that they hold nothing sacred. They are unrepentant nihilists. But as nasty as their behavior is, it is not without its benefits. When the gremlins come for Mrs. Deagle, they pose as Christmas carolers. Perhaps if she didn’t curse carolers and throw pitchers of water at them (as we see in a deleted scene), her life would be spared. In the same vein, maybe if Billy’s boss didn’t always scold him for being late, he wouldn’t be bludgeoned to death by clocks (another deleted scene available on the DVD). The gremlins seem to enjoy poetic justice, and by destroying the town’s constraining social structure, they are wiping the slate clean and setting its people free.

Good people don’t die in Gremlins. The Futtermans, as revealed by a TV newscast at the end of the movie, survive their snowplow accident. Maybe the gremlins just wanted to scare Mr. Futterman for being a xenophobe. Gerald (Judge Reinhold) is both Billy’s snide superior at the bank and a competitor for his girlfriend’s affections. He ends up locked in the bank vault, slightly mad – but is it because of the gremlins or because of his own paranoia and dependency on material possession? If the gremlins killed indiscriminately, the movie would teeter from its balance of comedy and horror. Adhering to the pattern of cautionary tale helps make this nasty little movie more palatable and fun.

Gremlins is a product of its time – before the age of computer graphics, and even before the perfection of animatronics. Chris Walas’ puppets are technological hits and misses. The range of expression is limited for Gizmo and the gremlins, and being puppets, their means of locomotion are even more limited. We never see Gizmo walk, and in some shots you can see the rods controlling the puppets’ arms. Do I care? Not at all. While Walas’ work may not hold up to today’s (outrageous) standards, it was certainly superior for its time, and more than makes up the difference when it comes to character. As limited as the puppets are, they are real — fabricated and operated by people on camera. The artistry and craftsmanship is immediately evident, especially in the mass choreography of the tavern sequence and inside the movie theatre, where the entire rooms are filled with gremlins. To populate the screen took more work and ingenuity than it would take today, and I’m not convinced that computer-generated effects would make it any more convincing.

Looking a lot like an old atomic-era comic book, Gremlins is washed in shadows and soft light, with deliberate use of colored lighting. Characters often appear bathed in red, blue or green. Dante takes advantage of canted angles, zooms, and other attention-getting cinematic devices that strengthen the film’s likeness to early comics and low-budget horror flicks. Showing his affinity for this source material, he includes several direct references in the film. At one point, Gizmo is watching Kevin McCarthy in the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers. When Billy is first attacked by a gremlin, it disappears through a ventilation duct dragging a strip of gauze — an homage to a specific shot in the Boris Karloff version of The Mummy. Robby the Robot, of Forbidden Planet fame, even makes a personal appearance.

Gremlins isn’t the kind of movie actors are remembered for, but they certainly pull their weight here. Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates play the all-American couple who take us through this adventure. As Gremlins isn’t a particularly character-driven movie, Galligan and Cates don’t have a heck of a lot to do. But there are a few moments when they rise to the challenge. Their first major scene together, where Billy gets the nerve to ask Kate out, is sweet and sincere without any drippy sentimentality. Juicier parts go to Hoyt Axton as Billy’s amateur inventor father, and to Polly Holliday (Flo on TV’s “Alice”) as the mean old Mrs. Deagle. Dick Miller is the laid-off, paranoid Mr. Futterman, given a nice speech about gremlins tinkering with machinery during the first world war, a foreshadowing of what lies in store for Kingston Falls. Howie Mandel provides the voice of Gizmo, while veteran voice actor Frank Welker brings the gremlins to life with his mischievous cackling.

Jerry Goldsmith won a Saturn award for his score to Gremlins. The score is a duplicitous one, first breathing life into the cheery town with light, jaunty orchestral fare. Goldsmith’s underscoring of Billy and Kate’s relationship is unabashedly innocent and sincere, adding to the couple’s wholesome charm. Gizmo has a happy little tune that’s worth humming, a far cry from the “gremlin rag”, a cacophonous ditty that embodies the creatures’ mischievousness and relentlessness. It’s a highly inventive and effective score. I particularly like how Goldsmith combines dissonant cords and cat howls to represent the gremlins’ shenanigans.

Gremlins is one of my favorite movies because it’s always fun to watch, no matter how old I am or where I am in life. It’s like a Grimm’s Fairy Tale for me, never losing its appeal. It’s a good, simple story, written with careful attention to tone and directed by a man who has a special love for the genre. Plus, I’ve always been a sucker for dark comedies. Maybe I’m just a gremlin at heart, always eager to pop someone’s balloon or snap their candy cane. In any case, for me, Christmas wouldn’t be the same without these little monsters.